365:2

Book Review #23: Water for Elephants by Sara Gruen

It’s been a while since I’ve read fiction that has absorbed me to the point of ignoring everyone else. I love books that utterly pull you in so that all you ant to do is lie on your bed, or curl up on the sofa and read. Water for Elephants was so good that despite it being on my Kindle, I didn’t even knit while I read and I finished it in 24 hours, which is no mean feat if there are 4 children and a house to deal with too!

The story follows Jacob, a young Polish origin vet in America who experiences a huge life changing tragedy and runs away to the circus, quite by accident. (As you do!) The book is a snapshot of life in a travelling circus in 1930’s America, the brutality, the incestuous relationships within people, the partition between performer and worker and the camaraderie that lies along side all the darker elements of a group of people pressurised into being together all the time. Jacob experiences all of these things, fresh from the real world and able to see things with both the clarity and naivety of being a young man with ideals and ethics that have not yet been corrupted.

Water for Elephants is also a love story, a tangled tug of war and an exploration of numerous twisted characters and relationships. It is beautifully narrated by the 90 year old (or 93!) Jacob, sitting out the end of his life in a care home and alongside the story of his past, is a delicately drawn picture of how life can end for even the most vital of people, people who had a youth which seemed it could never end in solitude. The brief and touching friendship that develops in that part of the story is heartbreakingly and heartwarming.

I’m incredibly grateful to Cara at Freckles Family who invited me to her book group and recommended this to me. I wouldn’t have missed it for the world.

365:1

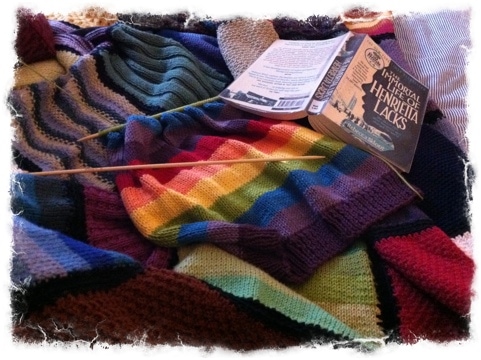

Book Review #22: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

I’m a total science numpty in most respects. I couldn’t wait to dump chemistry and physics and the only thing that has interested me in them since is the patient and fabulous science lessons HH does for the kids. I did keep going with Biology at school, largely because I had no choice, but I left it behind with a breath of relief at the end of GCSE and didn’t look back, which might seem odd for a child with a highly qualified and, in her field, rather well known research scientist for a mother. Both my siblings went on to do science based degrees, but I had utterly no interest. What interested me was people; I lapped up history and was engrossed in the Ethics GCSE I took, which sadly had no A Level equivalent in my school; I couldn’t get enough of how people lives or where or why and what changes them. People do really fascinate me. I spent a lot of my childhood and young adulthood acting or directing plays fairly successfully and to do that, putting yourself into the shoes of other people is a skill worth acquiring.

These two things make it both surprising and not at all surprising that I enjoyed this book so much. It tells the story of the HeLa cells, which were taken from the cervical tumour of Henrietta Lacks, a black women in 1950’s America. The cells, from a form of tumour previously unseen, were immortal; unlike other cell cultures where the cells had a natural shelf life even if they didn’t simply die from lack of the correct culturing procedures, Henrietta’s cells just kept on multiplying and dividing. It was a revolutionary breakthrough in science and they were shortly being shipped all over the world. From the work done with Henrietta’s cells came cancer treatments, HPV understanding, the potential to do IVF and so much more, along with incredible scientific misunderstanding and mistakes. To say I was surprised to find myself enjoying a book that described the history of cell culture is a a huge understatement.

What makes Rebecca Skloot’s book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, so extra-ordinarily good is not that it just tells that story. It tells the story of Henrietta, who died as a young mum thanks not only to her tumour but also in some ways due to the aggressive treatment she was subjected to. And it tells the very human story of all her children, most particularly her youngest daughter, who all grew up motherless, abused and most tragically, penniless while a multi-million dollar cell manufacturing business grew up around their mothers cells. While the world changed and factories were built to ship out her cells, her children couldn’t afford healthcare and were getting gradually sicker and angrier as knowledge began to filter back to them.

Most particularly of interest to me, not only because of the research I grew up alongside but also from the medical history I and my children have, was the thread that explored the birth of the notion of informed consent. It seems incredible that this is a recent concept. Only last week, 13 year old Fran was given the right to say no to her cleft data being held on a database. To think that is is hardly any time since people were experimented on without knowledge is quite incredible.

This is at once a personal and a global story, wrapped effortlessly into one compelling bundle. I’d say it is an absolute must read, a five star book of outlook changing proportions and truly fascinating alongside being deeply moving.